Unfolded

DATA browser 08

VOLUMETRIC REGIMES:

Material cultures of quantified presence

- Possible Bodies

- Blanca Pujals

- Jara Rocha

- Femke Snelting

- Sina Seifee

- Nicolas Malevé

- Simone C Niquille

- Maria Dada

- Phil Langley

- Helen V. Pritchard

- Kym Ward

- Spec

- Sophie Boiron

- Pierre Huyghebaert

- Romi Ron Morrison

- The Underground Division

- Manetta Berends

<insert variable geometry here>

First established in 2004, the DATA browser book series explores new thinking and practice at the intersection of contemporary art, digital culture and politics. The series takes theory or criticism not as a fixed set of tools or practices, but rather as an evolving chain of ideas that recognize the conditions of their own making. The term “browser” is useful here in pointing to the framing device through which data is delivered over information networks and processed by algorithms. Whereas a conventional understanding of browsing suggests surface readings and cursory engagement with the material, the series celebrates the potential of browsing for dynamic rearrangement and interpretation of existing material into new configurations that are open to reinvention.

Series editors:

Geoff Cox

Joasia Krysa

Volumes in the series:

DB 01 ECONOMISING CULTURE

DB 02 ENGINEERING CULTURE

DB 03 CURATING IMMATERIALITY

DB 04 CREATING INSECURITY

DB 05 DISRUPTING BUSINESS

DB 06 EXECUTING PRACTICES

DB 07 FABRICATING PUBLICS

DB 08 VOLUMETRIC REGIMES

This volume is produced with support from Liverpool John Moores University and London South Bank University.

DATA browser 08

VOLUMETRIC REGIMES:

Material cultures of quantified presence

- Possible Bodies

- Blanca Pujals

- Jara Rocha

- Femke Snelting

- Sina Seifee

- Nicolas Malevé

- Simone C Niquille

- Maria Dada

- Phil Langley

- Helen V. Pritchard

- Kym Ward

- Spec

- Sophie Boiron

- Pierre Huyghebaert

- Romi Ron Morrison

- The Underground Division

- Manetta Berends

DATA browser 08

VOLUMETRIC REGIMES: Material cultures of quantified presence

Edited by Possible Bodies

volumetricregimes.xyz

Published by

Open Humanities Press 2022

Copyright 🄯 2022 the authors

This is an open access book, licensed under the Collective Conditions for Re-Use (CC4r). You are invited to copy, distribute, and transform the materials published under these conditions, which means to take the implications of (re-)use into account. Read more about the license at

constantvzw.org/wefts/cc4r.en.html

Figures, text and other media included within this book may be under different copyright restrictions. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and obtain permission to reproduce visual material used in this publication. The editors would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book.

PDF freely available at

data-browser.net/db08.html

ISBN (print): 978-1-78542-116-7

ISBN (PDF): 978-1-78542-115-0

DATA browser series template

designed by Stuart Bertolotti-Bailey

Wiki-to-print development and F/LOSS redesign by Manetta Berends

Source files: git.vvvvvvaria.org/mb/

volumetric-regimes-book

The cover image is derived from Variable Geometry, an Open Source and cross-platform interpretation by Winnie Soon and Geoff Cox of the software app Multi by David Reinfurt. Multi updates the idea of the multiple from industrial production to the dynamics of the information age. Each cover presents an iteration of a possible 1,728 arrangements, each a face built from minimal typographic furniture, and from the same source code. o-r-g.com/apps/multi

and aesthetic-programming.net/

pages/2-variable-geometry.html

Contents

x, y, z: Dimensional axes of power

- Rigging Demons

Sina Seifee - Dis-orientation and its Aftermath

- x, y, z (4 filmstills)

- Invasive Imagination and its Agential Cuts

- The Extended Trans*feminist Rendering Program (wiki only)

The Underground Division

Parametric Unknowns: Hypercomputation between the probable and the possible

- Panoramic Unknowns

Nicolas Malevé - The Fragility of Life

A conversation with Simone C Niquille - Rehearsal as the ‘Other’ to Hypercomputation

Maria Dada - We hardly encounter anything that didn’t really matter

A conversation with Phil Langley - Comprehensive Features (wiki only)

A conversation with Phil Langley

somatopologies: On the ongoing rendering of corpo-realities

- Clumsy Volumetrics

Helen V. Pritchard - Somatopologies (materials for a movie in the making)

- Somatopologies: a guided tour II (wiki only)

- From Topology to Typography: A romance of 2.5D

Spec - Circluding

Kym Ward feat. Possible Bodies - MakeHuman

- Information for Users

Signs of clandestine disorder: The continuous after-math of 3D computationalism

- Endured Instances of Relation

An exchange with Romi Ron Morrison - The Industrial Continuum of 3D

- Signs of Clandestine Disorder in the Uniformed and Coded Crowds

- So-called Plants

Depths and Densities: Accidented and dissonant spacetimes

- Open Boundary Conditions: A grid for intensive study

Kym Ward - Depths and Densities: A bugged report

Jara Rocha - We Have Always Been Geohackers

The Underground Division - LiDAR on the Rocks

The Underground Division - Ultrasonic Dreams of Aclinical Renderings

Possible Bodies

- The So-called Lookalike

Manetta Berends - Publication History

- Biographies

- Item Index

Volumetric Regimes

Acknowledgements

Volumetric Regimes is the outcome of a collective process, inhabiting a thick network of para-academic solidarity between practitioners of different media, methods and tongues. We first of all would like to thank the interlocutors that have contributed to this book with their wonderful thinking, drawing, imagining and writing: Sophie Boiron, Maria Dada, Pierre Huyghebaert, Phil Langley, Nicolas Malevé, Romi Ron Morrison, Simone C Niquille, Helen V. Pritchard, Blanca Pujals, Sina Seifee and Kym Ward.

A huge thanks also to those who have been in conversation with the project at large, including: Ramon Amaro, Mercé Ardèvol, Tere Badia, Laura Benítez, Ona Bros, Gonzalo Correa, Emile Devereaux, Daphne Dragona, Marta Echaves, Laura Fernández, Sonia Fernández-Pan, Abelardo Gil-Fournier, Antye Guenther, Seda Gürses, Marie Lechner, Max and Franz Lehner, Alejandra López Gabrielidis, Zoumana Meïté, Martino Morandi, Paula Pin, Dennis Pohl, Anna Ramos, Carmen Romero Bachiller, SpiderAlex, Sophie Toupin, Peter Westenberg, Kathryn Yusoff, François Zajega and Adva Zakai.

The articulation of this research became a possibility during a fellowship at Akademie Schloss Solitude (Science and Business department) in Stuttgart and was further developed with a grant from the Flemish Government between 2017 and 2018. Other cultural and academic organisations supported us by inviting Possible Bodies for workshops, exhibitions, discussions and residencies: transmediale, Berlin; Hangar, Barcelona; Medialab Prado, Madrid; Constant, Brussels; Furtherfield, London; Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht; Festival Gelatina, Madrid; Universidad de la República and Casa Mario, Montevideo; Fuga, Barcelona; Goldsmiths University, London; Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid; La Gaîté Lyrique, Paris; Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; Radio MACBA, Barcelona; a.pass, Brussels; Fem TEK, Bilbao; FAP-TEK, Montevideo; University of Sussex, Brighton; Azala, Lasierra; and CSNI, London. Thank you participants, colleagues, comrades and also organizers, editors and curators with whom we had long and short exchanges over the years.

We want to acknowledge everyone who helped make this work available, accountable and legible, from on-line hosting, designing, peer-reviewing and transcribing to copy-editing. Thank you Geoff Cox and Joasia Krysa for your generous support as editors; Constant for providing us with an array of tools and practices plus a wide window to display our tilted sensibilities; Manetta Berends for the inspiring design collaboration and your comradeship; Nerea Calvillo, Eric Snodgrass, Magda Tyżlik-Carver for your invaluable comments combining rigour with enthusiasm; Mara Ittel, Fanny Wendt Höjer and Marc Herbst for your meticulous attention to detail and a special thanks to Helen V. Pritchard for their close companionship in the ongoing revolving of all matters.

We are deeply grateful for all the maintenance and care work involved in the making of first the artistic research of the Possible Bodies Inventory, and into a book later. Volumetric Regimes would not exist without the encouraging and supportive energies coming from companions, colleagues, friends, ancestors, and lovers of many sorts. Thank you all, for the inspiring and groundbreaking questions that you kept asking, full of constructive critique and sharp provocations. The depths and densities we need to embrace complexity with, would certainly not be possible without these thick currents of radical interdependencies.

Volumetric Regimes

Foreword

Blanca Pujals

We need, I believe, to engage a different kind of violence, a violence that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive, its calamitous repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales.[1]

The design of so-called bodies, territories or organisms, and of narratives which outline difference and The Other, impose binary separations. They produce slow a-temporal resonances throughout time, systematically replicating a western epistemology of management and control. These constructions allowed the contemporary technoscientific management of the environment and of our bodies, producing and reproducing algorithmic and systemic discrimination, which reveal different forms of structural differences and hegemonic fictions.

With-technology, “we” emerge as “us”. A hybrid human-machine-electron-organism, a planetary/time-space where cables, rare earth, bodies, soil, entities, liquids, particles, atmosphere and outer space are increasingly interconnected in a techno-organism that is speedily evolving, but which gathers in its source code a historical continuum of feedback loops.[2]

In his book Slow Violence, Rob Nixon describes processes characterized by violence that occur gradually and often in invisible ways.[3] Perhaps we can say that the parametric disassembling and reassembling of bodies and territories, is a process of slow violence that brings these problems to the present through their uninterrupted and increasingly sophisticated implementation.

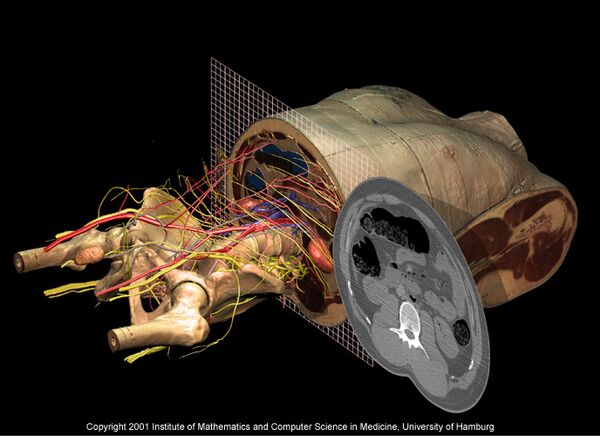

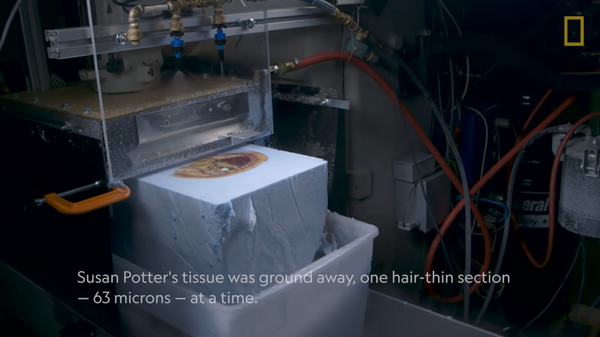

The scientific revolution, understood as a sociotechnical momentum in which the values of Modernity where implemented across western science disciplines, brought a transformation of the way the world was understood, starting off a massive taxonomization and abstraction of the environment. With processes of fragmentation, repeatability and simulation, the splitting of behaviors and organisms into data permeated into the volumetric design of bodies and territories. Since then, we find them embedded in computational software architectures, technologies which relentlessly scan matter in search of new forms of intervention. Hence, so-called bodies, territories, organisms, the organic and the inorganic can be managed for an efficient extraction and manipulation of materials and data, unveiling different forms of possession, property, rights and conflicts.

Statistical techniques of averaging and correlation from the nineteenth century introduced new photographic methods into their analyses, to catalogue organs and matter into static and isolated units. The pictures were organized and categorized by similar units in comparative tables, as for example Alphonse Bertillon’s bertillonage, or Francis Galton’s composites, where images, as slices, were overlapped to reveal a standard for disease, criminal type or race. Reading Volumetric Regimes, we can see how these techniques, initiated by the science of criminology, are nowadays introduced in the form of scanning and modelling technologies to disassemble and reassemble reality. Thus, these us-devices construct artificial borders, isolating groups of archetypes in a desperate will to contain nature’s behavior, analyzed and fixed through parametric systems into physical and digital technoscientific containment architectures. This provides a fantasy of enclosure, preventing the release and spread of an-Other’s influence. A system based on behavioral speculation and probability that creates both new threats and objectives within a retroactive system: a knowledge of the future by probabilistic determinism that continuously feeds a feedback loop of fears and threats, which shapes and reshapes our entire sociality.

In Volumetric Regimes we find, as a kind of resonance chamber full of case studies, an inventory of techniques used in the context of 3D computing to artificially design humanness, referred to as so-called bodies, so-called earth or so-called plants. Mechanisms such as rigging, agential cuts, slicing, dividing, dimensional axes of power, x,y,z, simulated environments, processes of modelling, capturing, rendering, printing and tracking unveil how scientific knowledge incorporated in computational tools is still based on dividing, separating and creating boundaries in a fictional composition of the tangible, in which the world is bounded and organized according to categories of hegemonic fictions. Through this organization, objects and organisms are disintegrated within extreme division and classification, and the isolation of the parts for their analysis erodes the uncategorized interrelations. Imposed official landscapes and bodies disregard the intra-actions “as a dynamism of forces in which all designated ‘things’ are constantly exchanging and diffracting, influencing and working inseparably.”[4]

Nevertheless, as the book also points out, new results concerning the origin of matter can lead us to reconsider older categories. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle states that one cannot simultaneously know both the exact position and exact momentum of a single particle. In addition, quantum entanglement means that the quantum state of each particle of a group cannot be described independently of the state of the others, including when particles are separated by a large distance, and so, also measurements affect the entangled system as a whole.[5] In this picture, matter moves increasingly toward a hybrid, ungraspable state. Quantum physics defies the system of observation born with the Modern project. Therefore, concepts such as uncertainty or entanglement, fundamental properties of the very elementary particles of matter (paradoxically resulting from splitting and smashing them to build the provisional Standard Model), can provide us with new generative possibilities and forms of social imagination.

Although liminal matter problematizes the matter of facts, “bodies” are still, and increasingly, locked within a regime of Modernity. As this book shows, this regime quietly and systematically spreads through contemporary 3D computing. Possible Bodies explores in Volumetric Regimes what the imaginary produced within that ontological and epistemological status of computational volumetrics does, and how it intervenes into power relationships. At the same time, they offer us a new imagine-action to rethink previous categorizations, by renaming them.[6] “Languaging” is one of the main tactics for unsettling Modern assumptions and rigidities. Vocabularies, verbalizations and discourse articulations provide with a rich realm for suspending the probable and extending the spectrum of what’s possible. “In other words”, language is understood as a mode for keeping complexity close while not aligning with the manners and grammars of a damaging world setting.

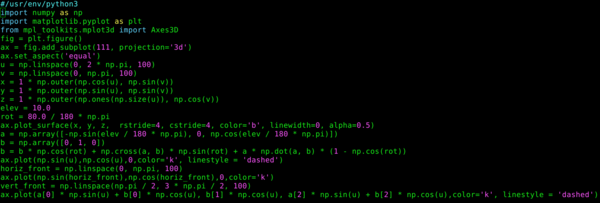

Perhaps, following the bug reports included in Volumetric Regimes, we can try to rethink the semantic layer of computational processes. As the image at the beginning of this text suggests, at the basis of computational design, we have mathematical code, a text which, as Possible Bodies proposes, we might need to re-imagine and re-write from scratch.

Notes

- ↑ Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2011).

- ↑ “Feedback occurs when outputs of a system are routed back as inputs as part of a chain of cause-and-effect that forms a circuit or loop. The system can then be said to feed back into itself. Simple causal reasoning about a feedback system is difficult because the first system influences the second and second system influences the first, leading to a circular argument.” “Feedback,” Wikipedia, accessed October 28, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feedback.

- ↑ Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.

- ↑ Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Half Way (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Quantum Entanglement, Wikipedia, accessed November 1, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_entanglement.

- ↑ Imagin-action (Imagina-ação): imagination as intervention in reproductive systems and invention of worlds; The “faculty”, or the operation of imagination in its collective and performative character of intervention in the world and not as a mere abstraction or pure speculative activity. In Portuguese, the word for “imagination” is “imaginação” and it contains the word “action”, “ação”. In this sense, thinking about the activity of imagining as an action, “ImaginAction” is an ethical, ontoepistemic and pragmatic approach, since it can lead us to other ways of conceiving the activity of imagining. Amilcar Packer, Office of Political Imagination, Brazil, 2016-now.

Volumetric Regimes

Volumetric Regimes: Material cultures of quantified presence

Volumetric Regimes

Possible Bodies (Jara Rocha, Femke Snelting)

What is going on with 3D!? This question, both modest and enormous, triggered the collaborative research trajectory that is compiled in this book. It was provoked by an intuitive concern about the way 3D computing quite routinely seems to render racist, sexist, ableist, speciest and ageist worlds.[1] Asking about what is up with 3D becomes especially urgent given its application in border-patrol devices, for climate prediction modeling, in advanced biomedical imaging or throughout the gamify-all approach of overarching industries, from education to logistics. The proliferating technologies, infrastructures and techniques of 3D tracking, modeling and scanning are increasingly hard to escape.

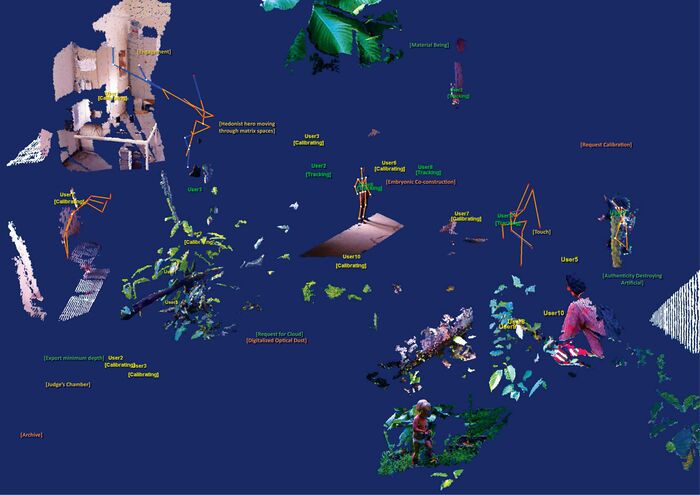

Volumetric Regimes emerges from Possible Bodies, a collaborative, multi-local and polyphonic project situated on the intersection of artistic and academic research, developing alongside an inventory of cases through writing, workshops, visual essays and performances. This publication brings together diverse materials from that trajectory as well as introduces new materials. It represents a rich and ongoing conversation between artists, software developers and theorists on the political, aesthetic and relational regimes in which volumes are calculated. At some point, we decided to fork Possible Bodies into The Underground Division to name the intensifying conversations on 3D-geocomputation with Helen V. Pritchard.[2] This explains why the attribution of the materials compiled in Volumetric Regimes takes multiple expressions of an extended we.[3]

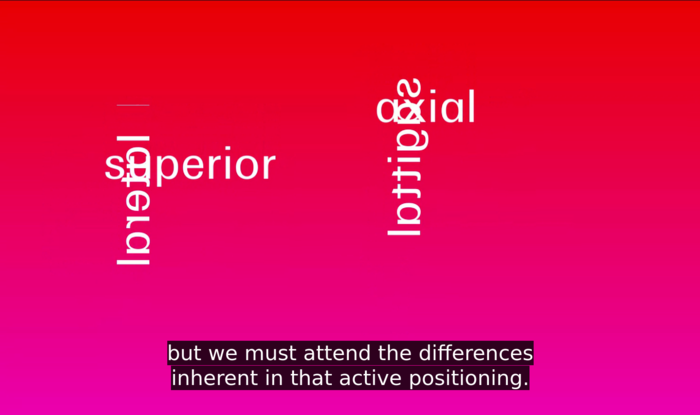

When we asked “What is going on with 3D?!” we generated many further questions, such as: Why is 3D now used as a synonym for volume-metrics. Or: how did the metric of volume become naturalized as 3D? How are volumes computed, accounted for and represented? Is the three-dimensional technoscientific organization of spaces, bodies or objects only about volume, or rather about the particular modes in which volume is culturally mobilized? How, then, are computational volumes occupying the world? What forms of power come along with 3D? How are the x, y and z axes established as linear carriers or variables of volume, by whom and why? If we take 3D as a noun, it points at the quality of being three-dimensional. But what if we follow the intuition of asking about “what is going on” and take 3D as an action, as an operation with implications for the way we can world otherwise? Can 3D be turned into a verb, at all? How can we at the same time use, problematize and engage with the cultures of volume-processing that converge under the paradigm of 3D?

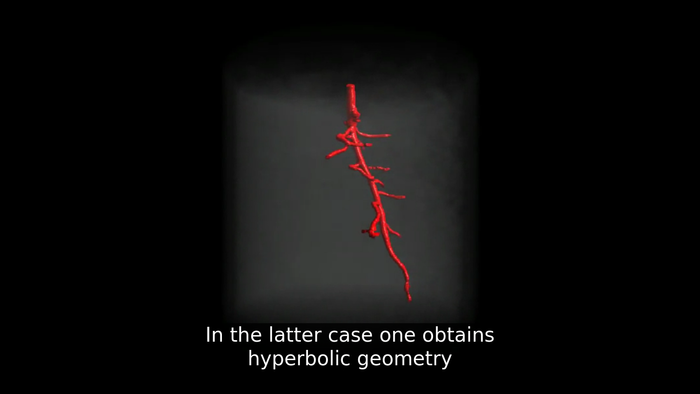

One important question we almost overlooked: What is volume, actually!? Let’s start by saying that as a representation of mass and of matter, volume is a naturalized construction, by means of calculation. “3D” then is a shortcut for the cultural means by which contemporary volume gets produced, especially in the context of computation. By persistently foregrounding its three distinct dimensions: depth, height and width, the concept of volume gets inextricably tied to the Cartesian coordinate system, a particular way of measuring dimensional worlds. The cases and situations compiled in this book depart from this important shift: in computation, volume is not a given, but rather an outcome, and volumetrics is the set of techniques to fabricate such outcome.

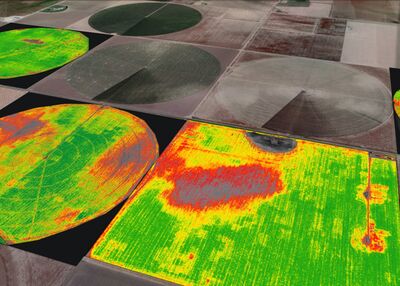

As a field oriented towards the technocratic realm of Modern technosciences, 3D computation has historically unfolded under “the probable” regimes of optimization, totalitarian efficiency, normalization and hegemonic world order.[4] Think of scanning the underground for extractable petro-fossil resources with the help of technologies first developed for brain surgery, and large scale agro-industrial 3D-applications such as spray installations enhanced with fruit recognition. In that sense, volumetrics is involved in sustaining the all too probable behavior of 3D, which is actively being (re)produced and accentuated by digital hyper-computation. The legacies and projections of industrial development leave traces of an ongoing controversy, where multiple modes of existence become increasingly unimaginable under the regime of the probable. Volumetric Regimes explores operational, discursive and procedural elements which might widen “the possible” in contemporary volumetrics.

Material cultures

This book is an inquiry into the material cultures of volumetrics. We did not settle on one specific area of knowledge, but rather stayed with the complexity of intricate stories that in one way or another involve a metrics of volume. The study of material cultures has a long tail which connects several disciplines, from archaeology and ethnography or design, which each bring their own methodological nuances and specific devices. Volumetric Regimes sympathizes with this multi-fold research sensibility that is necessary to think-with-matter. The framework of material cultures provides us with an arsenal of tools and vocabularies, interlocuting with, for example, New Feminist Materialisms, Science and Technology Studies, Phenomenology, Social Ecology or Cultural Studies.

The study of the material cultures of volumetrics necessitates a double-bind approach. The first bind relates to the material culture of volume. We need to speak about the volume that so-called bodies occupy in space from the material perspective of what they are made of – the actual conditions of their material presence and the implications of what space they occupy, or not. But we also need to speak about the material arrangements of metrics, the whole ecology of tools that participate in measuring operations. The second bind is therefore about the technopolitical aspects of knowledge production by measuring matter and of measured matter itself; in other words: the material culture of metrics.

The material culture of volumetrics and its internal double bind implies an understanding of technosocial relations as always in the making, both shaping and being shaped under the conditions of cultural formations. Being sensitive to matter therefore also involves a critical accountability towards the exclusions, reproductions and limitations that such formations execute. We decided to approach this complexity by assuming our response-ability with an inventory filled with cases and an explicitly political attitude.

The way matter matters has a direct affect on how something becomes a structural and structured regime, or rather how it becomes an ongoing contingent amalgamation of forces. There is no doubt that metrics can be considered to be a cultural realm of its own,[5] but what about the possibility of volume as a cultural field, infused by an apparatus of axioms and assumptions that, despite their rigid affirmations, are not referring to a pre-existent reality, but actually rendering one of their own?

In this book, we spend some quality time with the idea that volume, is the product of a specific evolution of material culture. We want to activate a public conversation, asking: How is power distributed in a world that is worlded by axes, planes, dimensions and coordinates, too often and too soon crystallizing abstractions in a path towards naturalizing what presences count where, for whom and for how long?

Volumetric regimes

We started this introduction by saying that volume is an outcome, not a given. Mass can (but does not have to) be measured by culturally-set operations like the calculation of its depth, or of its density. The volumes resulting from such measurement operations use cultural or scientific assumptions such as limit, segment or surface. The specific ways that volumetrics happen, and the modes that result in them crystallizing into axes and axioms, are the ones that we are trying to trace back and forth, to identify how they ended up arranging a whole regime of thought and praxis.

The contemporary regime of volumetrics, meaning the enviro-socio-technical politics and narratives that emerge with and around the measurement and generation of 3D presences, is a regime full of bugs, crawling with enviro-socio-technical flaws. Not neutral and also not innocent, this regime is wrapped up in the interrelated legacies and ideologies of neoliberalism, patriarchal colonial commercial capitalism, tied with the oligopolies of authoritarian innovation and technoscientific mono-cultures of proprietary hardware and software industries, intertwined with the cultural regimes of mathematics, image processing but also overly rigid vocabularies. In feminist techno-science, the relation between (human) bodies and technologies has had lots of attention, from the cyborg manifesto to more recent new materialist renderings of phenomena and apparatuses.[6] In the field of software studies, the “deviceful” entanglements between hegemonic regimes and software procedures have been thoroughly discussed,[7] while anti-colonial scholars have critiqued the ways that measuring or metrics align with racial capitalism and North-South divisions of power.[8] Thinking about the computation of volume is merely present in literature on the interaction of human and other-than-human bodies with machinic agents,[9] with the built environment[10] and its operative logics.[11]

What we have been looking for in the works listed above, and not always found, is the kind of diffuse rigor needed for a transformative politics that is a condition for non-binarism, of not settling, of being response-able in constant change.[12] This search triggered the intense interlocutions with the artists, activists and thinkers that have contributed to this book, and made us stick to polyhedric research methods. We’ve gone back to Paul B. Preciado, who taught us about the political fiction that so-called bodies are, a fleshy accumulation of archival data that keeps producing, reproducing and/or contesting the truths of power and their interlinked subjectivities.[13] Fired up for the worlding of different tech, we found inspiring unfoldings of computation and geological volumes in Kathryn Yusoff’s and Elizabeth A. Povinelli’s work, who insist on brave unpackings of Modern regimes all-the-way. We wondered about the voluminosity of “bodies” but also about their entanglement with what marks them as such, and how to pay attention to it. Reading Denise Fereirra da Silva’s email conversation with Arjuna Neuman about her use of the term “Deep Implicancy” rather than “entanglement”, we were struck by the relation between spatiality and separation she brings up: “Deep Implicancy is an attempt to move away from how separation informs the notion of entanglement. Quantum physicists have chosen the term entanglement precisely because their starting point is particles (that is, bodies), which are by definition separate in space.”[14] Syed Mustafa Ali and David Golumbia separate computation from computationalism to make clear that while computation obviously sediments and continues colonial damages, this is not necessarily how it needs to be (and it necessarily needs to be otherwise). Interlocutions with the deeply situated work of Seda Gürses,[15] operating on the discipline of computation from the inside, sparked with the energy of queer thinkers and artists Zach Blas and Micha Cárdenas[16] and more recently Loren Britton, and Helen V. Pritchard in For CS.[17] We are grateful for their critical problematizations of the ever-straightening protocols which operate in every corner where existence is supposed to happen.

The shift to understanding volume as an outcome of sociotechnical operations, is what helps us activate the critical revision of the regimes of volumetry and their many consequences. If volume does not exist without volumetric regimes, then the technopolitical struggle means to scrutinize how metrics could be exploded, (re)designed, otherwise implemented, differently practiced, (de)bugged, interpreted and/or cared for.

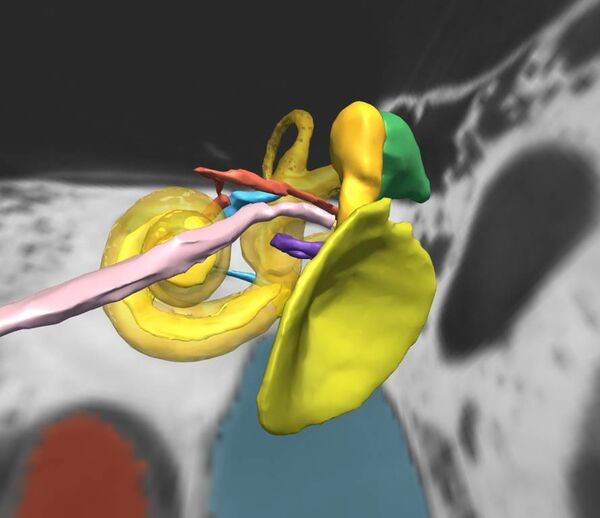

Quantified presence

Volumetric Regimes is also our way to build capacities for a response to the massive quantification of presences existing in computed space-times. Such response-ability needs to be multi-faceted, due to the process of manipulation that quantifying presences apply to presence itself as an ontological concern. The fact that something can exist and be accountable in a virtual place, or that something which is present in a physical space can re-appear or be re-presented in differently mediated conditions, or not at all, is technically produced through supposedly efficient gestures such as clear-cut incisions, separating boundaries, layers of segmentation, regions of interest and acts of discretization. The agency of these operations is more often than not erased after the fact, providing a nauseating sense of neutrality.

The project of Volumetric Regimes is to think with and towards computing-otherwise rather than to side with the uncomputable or to count on that which escapes calculation. Flesh, complexity and mess are already-with computation, somehow simultaneous and co-constituent of mess. The spaces created by the tension between matter and its quantification, provide with a creative arena for the diversification of options in the praxis of 3D computation. Qualitative procedures like intense dialog, hands-on experiments, participant observation, speculative design and indeterminate protocols help us understand possible research attitudes in response to a quantify-all mono-culture, not succumbing to its own pre-established analytics. Could “deep implicancy” be where computing otherwise happens, by means of speculation, indeterminacy and possibility? Perhaps such praxis is already located beyond or below normed actions like capturing, modeling or tracking that are all so complicit with the making of fungibility.[18]

The specific form of quantification that is at stake in the realm of volume-metrics, is datafication. The computational processing, displacing and re-arranging of matter through volumetric techniques participates in what The Invisible Committee called the crisis of presence, which can be observed at the very core of the contemporary ethos.[19] We connect with their concerns about the way present presences are rendered, or not. How to value what needs to count and be counted or what is in excess of quantification, via the exact same operation, in a politicized way. In other words, a politics of reclaiming quantification is a praxis towards a politicized accountability for the messiness of all techniques that deal with the thickness of a complex world. Such praxis is not against making cuts as such, but rather commits to being response-able with the gestures of discretion and not making final finite gestures, but reviewable ones. Connecting to quantification in this manner, is a claim for forms of accountable accountability.[20]

Aligning ourselves with the tradition of feminist techno-sciences, Volumetric Regimes: Material cultures of quantified presence stays with the possible (possible tools, methods, practices, materializations, agencies, vocabularies) of computation, demanding complexity while queering the rigidity of their fixing of items, discrete and finite entities in too fast moves towards truth and neutrality.

In this publication we try by all means to disorient the assumption of essentialist discreteness and claims for the thickening of qualitative presence in 3D computation realms. In that sense, Volumetric Regimes could be considered as an attempt to do qualitative research on the quantitive methods related to the volumetric-occupation of worlds.

Polyhedric research methods

In terms of method, this book benefits from several polyhedric forces that when combined, form a prismatic body of disciplinarily uncalibrated but rigorous research. The study of the complex regimes that rule the worlds of volumes, necessitated a few methodological inventions to widen the spectrum of how computational volumetrics can be studied, described, problematized and reclaimed.[21] That complexity is generated not only by the different areas in which measuring volumes is done, but also because it is a highly crowded field, populated by institutional, commercial, scientific, sensorial and technological agents.

One polyhedric force is the need for direct action and informed disobedience applied to research processes. We have often referred to our work as “disobedient action-research”, to insist on a mode of research that is motivated by situated, ad-hoc modes of producing and circulating knowledge. We committed to a non-linear workflow of writing, conversing and referencing, to keep resisting developmental escalation, but rather to hold on to an iterative and sometimes recursive flow. While in every discipline there are people and practices opening, mixing, expanding, challenging, and refusing traditional methods, research involving technology is too often ethically, ontologically, and epistemologically dependent on a path from and towards universalist enlightenment, aiming to eventually technically fixing the world. This violent and homogenizing solutionist attitude stands in the way of a practice that, first of all, needs to attend to the re-articulation and relocation of what must be accounted for, perhaps just by proliferating sensibilities, issues, demands, requests, complaints, entanglements, and/or questions.[22]

A second polyhedric force is generated by the playful intersection of artistic and academic research in the collaborative praxis of Possible Bodies. It materializes for example in uncommon writing and the use of made-up terminology, but also in the hands-on engagement with tools, merging high and low tech, learning on the go, while attending to genealogies that arranged them in the here-now. You will find us smuggling techniques for knowledge generation from one domain to another such as contaminating ethnographic descriptions with software stories, mixing poetics with abnormal visual renders, blurring theoretical dissertations with industrial case-studies and so forth.

Trans*feminism is certainly a polyhedric dynamic at work, in mutual affection with the previous forces. We refer to the research as such, in order to convoke around that star (*) all intersectional and intra-sectional aspects that are possibly needed.[23] Our trans*feminist lens is sharpened by queer and anti-colonial sensibilities, and oriented towards (but not limited to) trans*generational, trans*media, trans*disciplinary, trans*geopolitical, trans*expertise, and trans*genealogical forms of study. The situated mixing of software studies, media archaeology, artistic research, science and technology studies, critical theory and queer-anticolonial-feminist-antifa-technosciences purposefully counters hierarchies, subalternities, privileges and erasures in disciplinary methods.

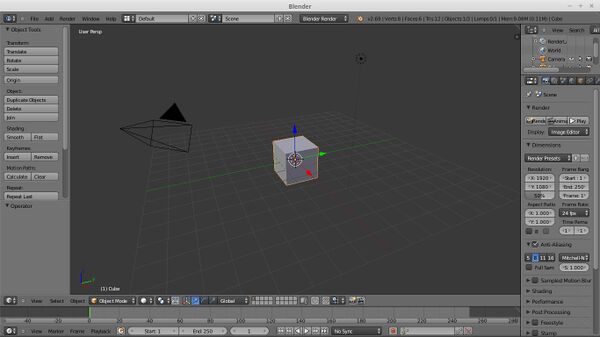

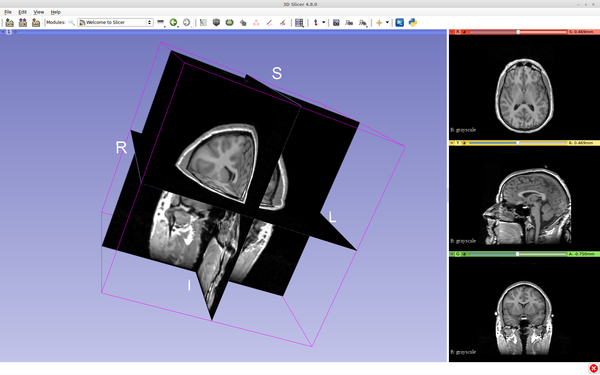

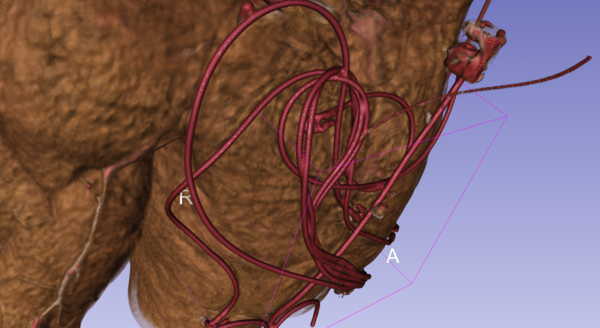

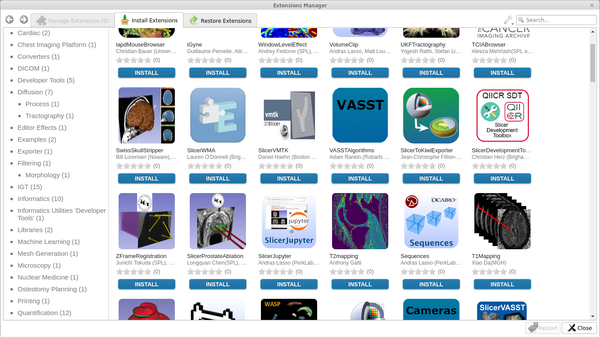

The last polyhedric force is generated by our politicized attitude towards technological objects. This book was developed on a wiki, designed with Free, Libre and Open Source software (FLOSS) tools and published as Open Access.[24] Without wanting to suggest that FLOSS itself produces the conditions for non-hegemonic imaginations, we are convinced that its persistent commitment to transformation can facilitate radical experiments, and trans*feminist technical prototyping. The software projects we picked for study and experimentation such as Gplates,[25] MakeHuman,[26] and Slicer[27] follow that same logic. It also oriented our DIWO attitude of investigation, preferring low-tech approaches to high-tech phenomena and allowing ourselves to misuse and fail.

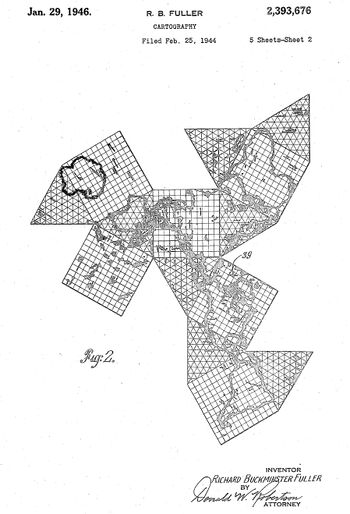

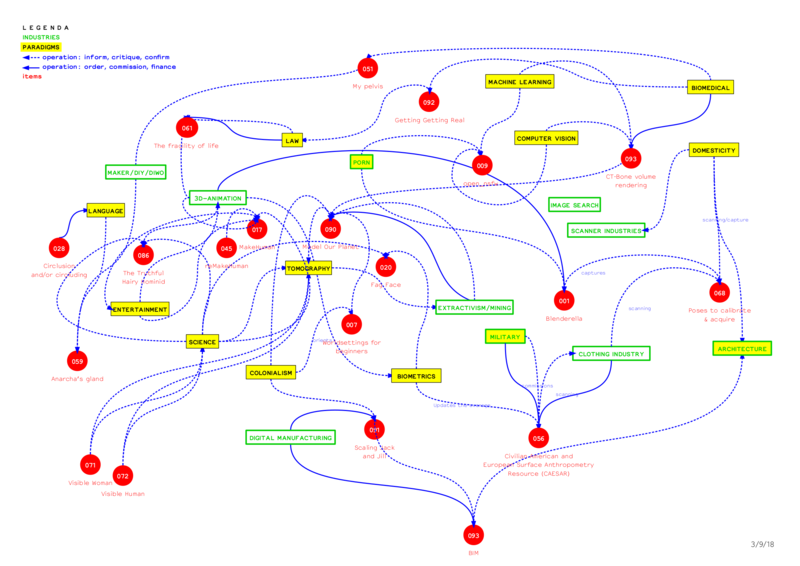

To give an ongoing account of the structural formations conditioning the various cultural artifacts that are co-composed through scanning, tracking and modeling, we settled for inventorying as a central method. The items in the Possible Bodies inventory do not rarefy these artifacts, as would happen through the practice of collecting, or by pinning them down, as in the practice of cartography, or rigidly stabilize them, as might be a risk through the practice of archiving.[28] Instead, the inventorying is about continuous updates, and keeping items available. The inventory functions as an additional reference system for building stories and vocabularies; items have been used for multiple guided tours, both written and performed.[29] Being aware of its problematic histories of commercial colonialism, the praxis of inventorying needs to also be reoriented towards just and solidary techniques of semiotic-material compilation.[30]

The writing of bug reports is a specific form of disobedient action research which implies a systematic re-learning of the very exercise of writing, as well as a resulting direct interpellation to the communities that develop software, by its own means and channels. Bug reporting, as a form of technical grey literature, makes errors, malfunctions, lacks, or knots legible; secondly, it reproduces a culture of a public interest in actively taking-part in contemporary technosciences. As a research method, it can be understood as a repoliticization and cross-pollination of one of the key traditional pillars of scientific knowledge production: the publishing of findings.

Technical expertise is not the only knowledge suitable for addressing the technologically produced situations we find ourselves in. The term clumsy computing describes a mode of relating to technological objects that is diffuse, sensitive, tentative but unapologetically confident.[31] Such diffuseness can be found in the selection of items in the inventory,[32] in the deliberate use of deported terminology, in the amateur approach to tools, in the hesitation towards supposedly ontologically-static objects of study, in the sudden scale jumps, in the radical disciplinary un-calibration and in our attention to porous boundaries of sticky entities.[33]

The persistent use of languaging formulas problematizes the limitations of ontological figures. For example the repeated use of “so-called” for “bodies” or “plants” is a way to question the various methods whereby finite, specified and discrete entities are being made to represent the characteristics of whole species, erasing the nuances of very particular beings.[34] Combinatory terms such as “somatopologies” play a recombinatory game to insist on the implications of one regime onto another.[35] Turning nouns into verbs such as using “circlusion” as “circluding”, is a technology that forces language to operate with different temporary tenses and conjugations, refusing the fixed ontological commingling that naming implies.[36]

Interlocution has ruled the orientations of this inquiry that was collective by default: by affecting and being affected by communities of concern in different locations, the research process changed perspectives, was infused by diverse vocabularies and sensibilities and jumped scales all along. The conversations brought together in Volumetric Regimes stuck with this principle of developing the research through an affective network of comrades, companions, colleagues and collaborators, based on elasticity and mutual co-constitution.

README

Volumetric Regimes experiments with various formats of writing, publishing and conversing. It compiles guided tours, peer-reviewed academic texts, speculative fiction, pamphlets, bug reports, visual essays, performance scripts and inventory items. It is organized around five chapters, that each rotate the proliferating technologies, infrastructures and techniques of 3D tracking, modeling and scanning differently. Although they each take on the question “What is going on with 3D?!” through a distinct axiology of technology, politics and aesthetics, they do not assume nor impose a specific order for the reader. Each chapter includes an invited contribution that proposes a different orientation, offers a Point of View (POV) or triggers a perspective on the material-discursive entanglements in its own way.

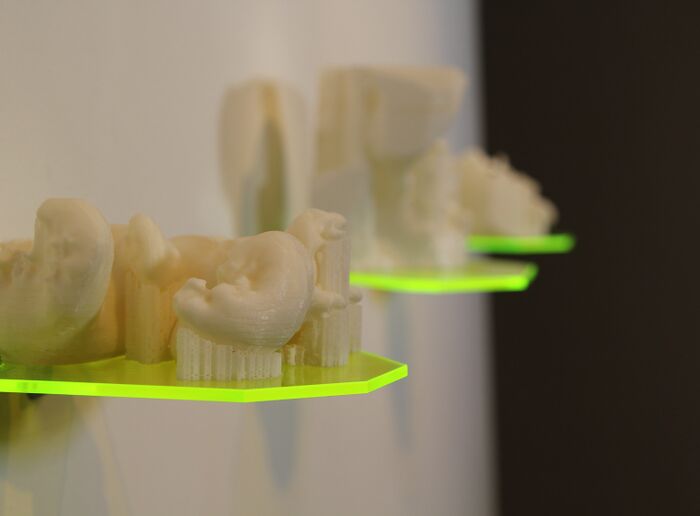

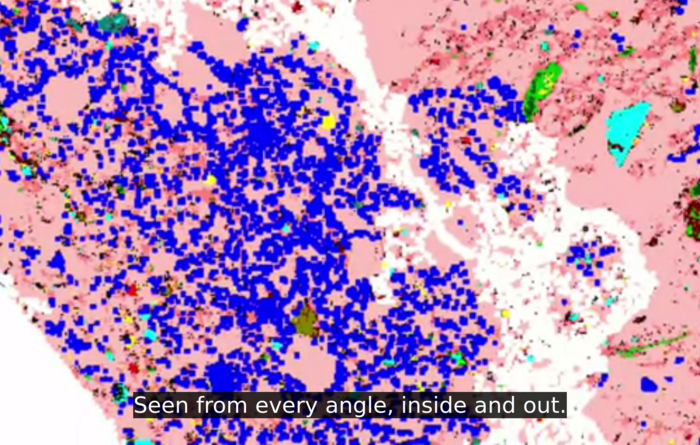

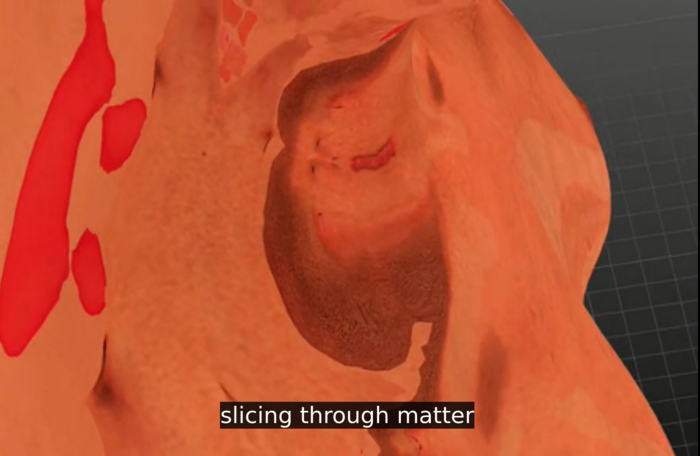

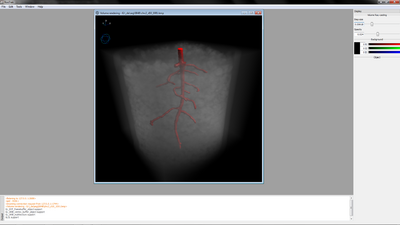

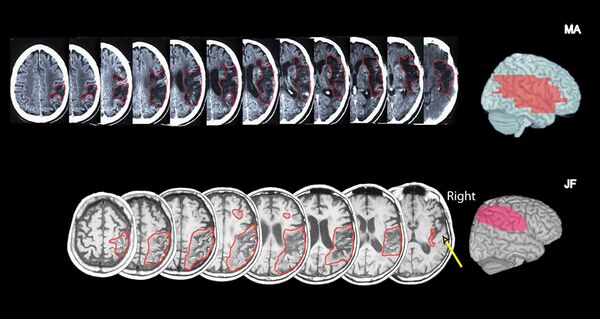

x, y, z: Dimensional Axes of Power takes on the building blocks of 3D: x, y and z. The three Cartesian axes both constrain and orient the chapter, as they do for the space of possibility of the volumetric. It takes seriously the implications of a mathematical regime based on parallel and perpendicular lines, and zooms in on the invasive operations of virtual renderings of fleshy matter, but also calls for queer rotations and disobedient trans*feminist angles that can go beyond the rigidness of axiomatic axes within the techno-ecologies of 3D tracking, modeling and scanning. The chapter begins with a contribution by Sina Seifee, who in his text “Rigging Demons” draws from an intimate history with the technical craft-intense practice of special effects animation, to tell us stories of visceral non-mammalian animality between love and vanquish. The chapter continues with a first visit to the Possible Bodies inventory that sets-up the basic suspicions on what is of value in rendered and captured worlds, following the thread of dis-orientation as a way to think through the powerful worldings that are nevertheless produced by volumetrics. “Invasive Imagination and its agential cut” reflects on the regimes of biomedical imaging and the volumetrization of so-called bodies.

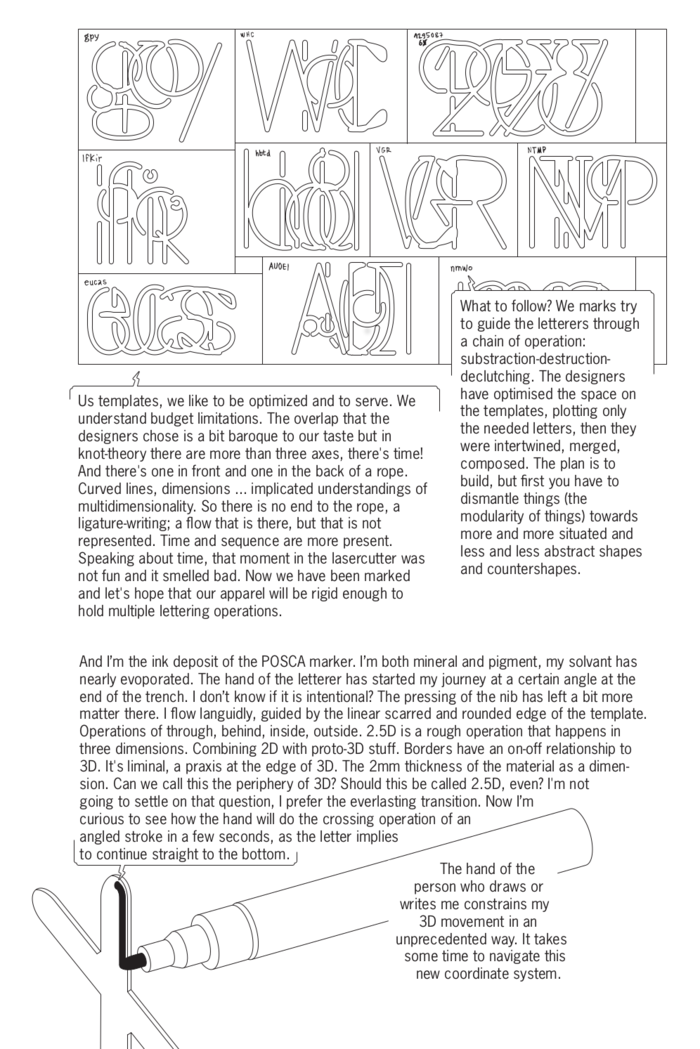

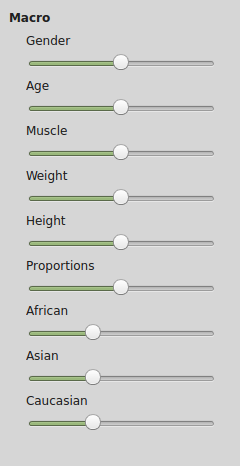

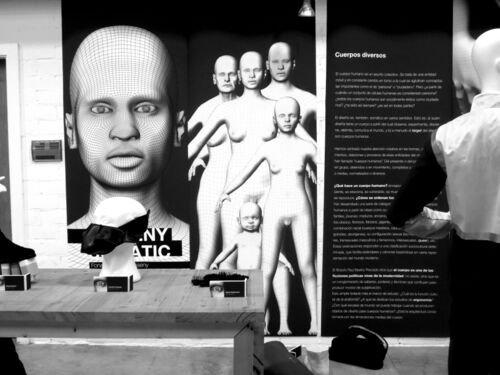

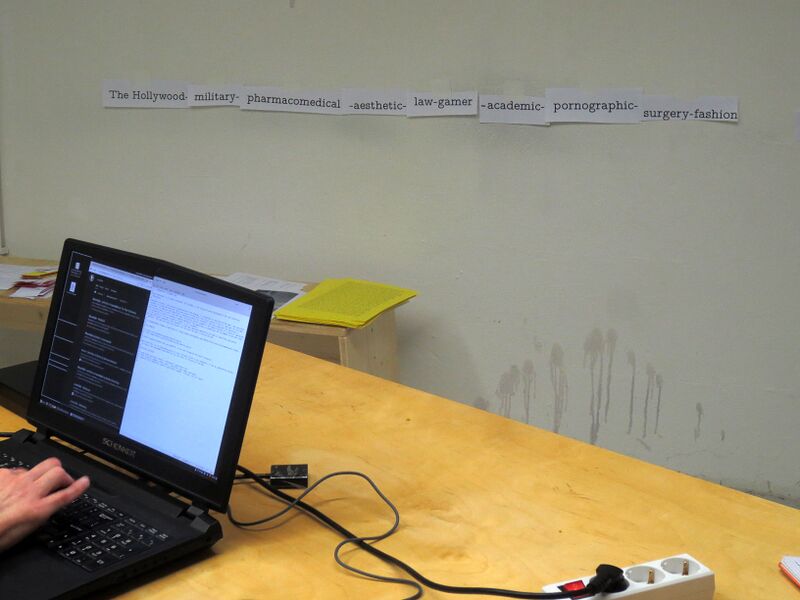

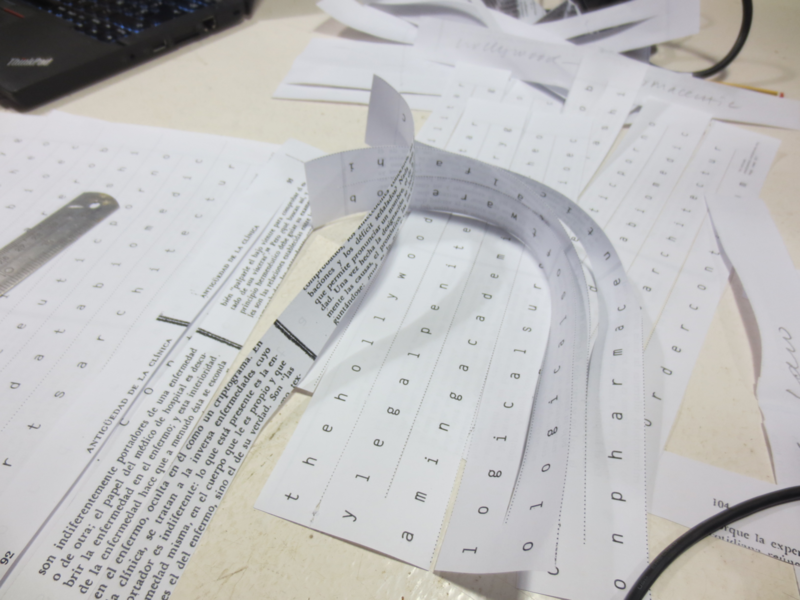

Somatopologies: On the ongoing rendering of corpo-realities opens up all the twists in epistemologies and methodologies triggered by Volumetric Regimes in the somatic realm. As a notion, “somatopologies” converges the not-letting-go of Modern patriarchocolonial apparatuses of knowledge production like mathematics or geometry, specifically focusing on an undisciplined study of the paradigm of topology. By opening up the conditions of possibility, soma-topologies is a direct claim for other ontologies, ethics, practices and crossings. The chapter opens with “Clumsy Volumetrics” in which Helen V. Pritchard follows Sara Ahmed’s suggestion that “clumsiness” might form a queer and crip ethics that generates new openings and possibilities. “Somatopologies (materials for a movie in the making)” documents a series of installations and performances that mixed different text sources to cut agential slices through technocratic paradigms in order to create hyperbolic incisions that stretch, rotate and bend Euclidean nightmares and Cartesian anxieties. “Circluding” is a visual/textual collaboration with Kym Ward on the potential of a gesture that flips the order of agency without separating inside from outside. In “From Topology to Typography: A romance of 2.5D”, Sophie Boiron and Pierre Huyghebaert open up a graphic conversation on the almost-volumetrics that precede 3D in digital typography and finally the short text “MakeHuman” and the pamphlet “Information for Users” take on the implications of relating to 3D-modelled-humanoids.

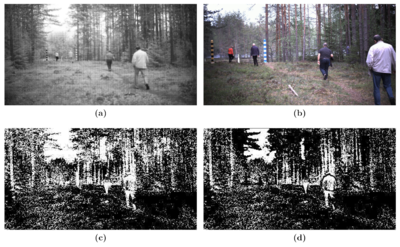

The vibrating connections between hyper-realism and invention, re-creation and simulation, generation and parametrization are the inner threads of a chapter titled Parametric Unknowns: Hypercomputation between the probable and the possible. What’s in the world and what is processed by mechanisms of volumetric vision differs only slightly, offering a problematic dizzying effect. The opening of the chapter is in the hands of Nicolas Malevé, who offers a visual ethnography of some of the interiors and bodies that made computational photography into what it became. Not knowing everything yet, the panoramization of intimate atmospheres works as an exercise to study the limits between the flat surfaces of engineering labs and the dense worlds behind their scenes. “The Fragility of Life” is an excuse to enter into the thick files compiled by designer-researcher Simone C Niquille on the digital post-production of truth. Somehow in line with that, Maria Dada provides an overview of how different training and rehearsing are, especially in the gaming industry that makes History with a capital H. And finally, a long-term conversation with Phil Langley questions the making of too fast computational moves while participating in architectural and infrastructural materializations.

Signs of Clandestine Disorder: The continuous aftermath of 3D-computationalism follows the long tail of volumetric techniques, technologies and infrastructures, and the politics inscribed within. The chapter’s title points to “computationalism”, a direct reference to Syed Mustafa Ali’s approach to decolonial computing.[37] The other half is a quote from Alphonso Lingis, which invokes the non-explicit relationality between elements that constitute computational processes.[38] In that sense, it contrasts directly with the discursive practice of colonial perception that Ramon Amaro described as “self maintaining in its capacity to empirically self-justify.”[39] The chapter opens with “Endured Instances of Relation” in which Romi Ron Morrison reflects on specific types of fixity and fixation that pertain to volumetric regimes, and the radical potential of “flesh” in data practices, while understanding bodies as co-constructed by their inscriptions, as a becoming-with technology. The script for the workshop “Signs of clandestine disorder for the uniformed and codified crowd” is a generative proposal to apply the mathematical episteme to lively matters, but without letting go of its potential. In “So-called Plants” we return to the inventory for a vegetal trip, observing and describing some operations that affect the vegetal kingdom and volumetrics.

The last chapter is titled Depths and Densities: Accidented and dissonant spacetimes. It proposes to shift from the scale of the flesh to the scale of the earth. The learnings from the insurgent geology of authors like Yusoff triggered many questions about the ways technopolitics cut the vertical and horizontal axis and that limit the spectrum of possibilities to a universalist continuation of extractive modes of existence and knowledge production. The contribution by Kym Ward, “Open Boundary Conditions”, offers a first approach to her situated intensive study of the crossings between volumetrics and oceanography, from the point of view of the Bidston Observatory in Liverpool. From this vantage point she articulates a critique on technosciences, and provides with an overview of possible affirmative areas of study and engagement. In “A Bugged Report”, the filing of bug reports turns out to be an opportune way to react to the embeddedness of anthropocentrism in geomodeling software tools, different to, for example, technological sovereignty claims. “We Have Always Been Geohackers” continues that thinking and explores the probable continuation of extractive modes of existence and knowledge production in software tools for rendering tectonic plates. The workshop script for exercising an analog LiDAR apparatus is a proposal to experience these tensions in physical space, and then to discuss them collectively. The chapter ends with “Ultrasonic Dreams of Aclinical Renderings”, a fiction that speculates with hardware on the possibilities for scanning through accidented and dissonant spacetimes.

Notes

- ↑ This intuition surfaced in GenderBlending, a worksession organized by Constant, association for art and media based in Brussels, in 2014. Body hackers, 3D theorists, game activists, queer designers and software feminists experimented at the contact zones of gender and technology. Starting from the theoretical and material specifics of gender representations in a digital context, GenderBlending was an opportunity to develop prototypes for modelling digital bodies differently. “Genderblending,” Constant, accessed October 6, 2021, https://constantvzw.org/site/-GenderBlending,190-.html.

- ↑ “The Underground Division,” accessed October 20, 2021, http://ddivision.xyz.

- ↑ We decided not to flatten or erase these porous attributions. Therefore you will find a multiplicity of authorial takes throughout this book: Possible Bodies, Possible Bodies (Jara Rocha, Femke Snelting), Possible Bodies feat. Helen V. Pritchard, Jara Rocha, and Femke Snelting, Kym Ward feat. Possible Bodies, Jara Rocha, The Underground Division and The Underground Division (Helen V. Pritchard, Jara Rocha, Femke Snelting).

- ↑ See “Item 127: El Proyecto Moderno / The Modern Project,” The Possible Bodies Inventory, 2021.

- ↑ See, for example Alfred W. Crosby, The Measure of Reality: Quantification in Western Europe, 1250–1600 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- ↑ Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Some of the publications in the field of Software Studies that have done this work include Matthew Fuller, Behind the Blip: Essays on the Culture of Software (Brooklyn: Autonomia, 2003), Adrian Mackenzie, Cutting Code: Software and Sociality (New York: Peter Lang, 2006), Wendy Chun, Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2011), Matthew Fuller, and Andrew Goffey, Evil Media (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2012), Geoff Cox, and Alex McLean, Speaking Code: Coding as Aesthetic and Political Expression (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2012) and more recently Winnie Soon, and Geoff Cox Aesthetic Programming (London: OHP, 2020).

- ↑ From Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “Race and/as Technology; or, How to Do Things to Race,” Camera Obscura 70, 24(1) 7-35, to Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Hoboken: Wiley, 2019).

- ↑ Stamatia Portanova, Moving Without a Body (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2012).

- ↑ Luciana Parisi, Contagious Architecture: Computation, Aesthetics, and Space (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2013).

- ↑ Aud Sissel Hoel, and Frank Lindseth, “Differential Interventions: Images as Operative Tools,” in Photomediations: A Reader, eds. Kamila Kuc and Joanna Zylinska (Open Humanities Press, 2016), 177-183.

- ↑ “There are no solutions; there is only the ongoing practice of being open and alive to each meeting, each intra-action, so that we might use our ability to respond, our responsibility, to help awaken, to breathe life into ever new possibilities for living justly.” Karen Barad, Meeting the universe halfway.

- ↑ Paul B. Preciado calls the fictive accumulation a somathèque. “Interview with Beatriz Preciado, SOMATHEQUE. Biopolitical production, feminisms, queer and trans practices,” Radio Reina Sofia, July 7, 2012, https://radio.museoreinasofia.es/en/somatheque-biopolitical-production-feminisms-queer-and-trans-practices.

- ↑ Denise Ferreira da Silva, and Arjuna Neuman, “4 Waters: Deep Implicancy” (Images Festival, 2019) http://archive.gallerytpw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Arjuna-Denise-web-ready.pdf.

- ↑ For example in her important work on understanding shifts in the practice of software production. Seda Gürses, and Joris Van Hoboken, “Privacy after the Agile Turn,” eds. Jules Polonetsky, Omer Tene, and Evan Selinger, Cambridge Handbook of Consumer Privacy (Cambridge University Press, 2018), 579-601.

- ↑ Zach Blas, and Micha Cárdenas, “Imaginary Computational Systems: Queer technologies and transreal aesthetics,” AI & Soc 28 (2013): 559–566.

- ↑ Loren Britton, and Helen Pritchard, “For CS,” interactions 27, 4 (July - August 2020), 94–98.

- ↑ See: Romi Ron Morrison, “Endured Instances of Relation, an exchange,” in this book.

- ↑ The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2015).

- ↑ Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway.

- ↑ Celia Lury, and Nina Wakeford, Inventive Methods: the Happening of the Social (Milton Park: Routledge, 2013).

- ↑ See: The Underground Division (Helen V. Pritchard, Jara Rocha, and Femke Snelting), “We have always been geohackers,” in this book.

- ↑ “The asterisk hold off the certainty of diagnosis.” Jack Halberstam, Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), 4.

- ↑ See: Manetta Berends, “The So-Called Lookalike,” in this book.

- ↑ See: Jara Rocha, “Depths and Densities: A bugged report,” in this book.

- ↑ See: Jara Rocha, Femke Snelting, “MakeHuman,” in this book.

- ↑ See: Jara Rocha, Femke Snelting, “Invasive Imagination and its Agential Cuts,” in this book.

- ↑ See: Jara Rocha, Femke Snelting, “Disorientation and its aftermath,” in this book.

- ↑ Possible Bodies, “Inventorying as a method,” The Possible Bodies Inventory, https://possiblebodies.constantvzw.org/inventory/?about.

- ↑ See: Jara Rocha, Femke Snelting, “Disorientation and its aftermath,” in this book.

- ↑ See: Helen Pritchard, “Clumsy Computing”, in this book.

- ↑ The Possible Bodies Inventory, accessed October 20, 2021,

https://possiblebodies.constantvzw.org/inventory - ↑ Andrea Ballestero, “The Underground as Infrastructure? Water, Figure/Background Reversals and Dissolution in Sardinal,” ed. Kregg Hetherington, Infrastructure, Environment and Life in the Anthropocene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).

- ↑ See: “So-called Plants,” in this book.

- ↑ See: “Somatopologies,” in this book.

- ↑ See: Kym Ward feat. Possible Bodies, “Circluding,” in this book.

- ↑ Syed Mustafa Ali, “A Brief Introduction to Decolonial Computing,” XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, 22(4) (2016): 16-21.

- ↑ “We walk the streets among hundreds of people whose patterns of lips, breasts, and genital organs we divine; they seem to us equivalent and interchangeable. Then something snares our attention: a dimple speckled with freckles on the cheek of a woman; a steel choker around the throat of a man in a business suit; a gold ring in the punctured nipple on the hard chest of a deliveryman; a big raw fist in the delicate hand of a schoolgirl; a live python coiled about the neck of a lean, lanky adolescent with coal-black skin. Signs of Clandestine Disorder in the Uniformed and Coded Crowds.” Alphonso Lingis, Dangerous Emotions (University of California Press, 2000), 141.

- ↑ Ramon Amaro, “Artificial Intelligence: warped, colorful forms and their unclear geometries,” in Schemas of Uncertainty: Soothsayers and Soft AI, eds. Danae Io and Callum Copley (Amsterdam: PUB/Sandberg Instituut, 2019), 69-90.

x, y, z: Dimensional axes of power

x, y, z

Rigging Demons

Sina Seifee

Coming from the pirate infrastructure of Iran, computer black-market by default, sometime in my early youth I installed a cracked version of Maya (3D software developed at that time by Alias Wavefront). I was making exploratory locomotor behaviors, scripting postural coordinations, kinesthetic structures, and automated skeletal rigs. Soon after, doing simple computer graphics hacks in 3D became a pragmatic experimentation habit. Now looking back, I think it was a way for me to extend a line of flight. Doing autonomous affective pragmatic experiments in a virtual microworld helped me to exit my form of subjectivity. Something that I will unpack in the following text as counter dispossession through engagement with the phantom limb.

“Counter” is perhaps not quite the right word, play is more accurate. Because play happens always on the edge of double bind experience (a condition of schizophrenia). Our relationship with media technologies is a “double bind patterning”, a system of layered contradictions that is experienced as reality. Following Katie King’s rereading of her teacher Gregory Bateson, double bind happens when something is prohibited at one level of meaning or abstraction (within a particular communicating channel), while something else is required (at another level) that is impossible to effect if the prohibition is honored.[1] Our relationship with the phantom limb is at once experienced at the level of terror (being haunted by it) and companionship (extend one’s being in the world).

This text develops a system of references and compositional attunement to a technical craft-intense practice called rigging in computer graphics. My aim is to apply the idea of volumetric regimes to rigging, and its media specificities, as one style of animating volumetric bodies particularly naturalized in the animation industry and its techno-culture. I will highlight one of its occurrences in film, namely the visual effects that are associated with disintegration of “demons” in the TV-series Charmed and will propose the disintegrating demon body as a multi-sited loci of meaning. Multi-sites require inquiries in more than one location, also combining different types of location: geographical, digital, temporal, and also demonological. Disintegrating demons are less interesting as a subject for analogies of body politics and more as an object of computerized zoomorphic experimentations. They are performed in specific ways in digital circumstances, which I refer to as doing demons.

I am going to take myself as an empirical access point to think about the ecology of practices[2] or the ecology of minds[3] that involve computerized animated nonhumans, and arrest my digital memories as a molecular material history, in order to share my sensoria among species that shape our relationships with machines. This text is also an exercise in accounting for my own technoperceptual habituations. The technoperceptual can refer to the assemblages of thoughts, acts of perception and of consumption that I am participating with—a term I learnt from Amit Rai in his fabulous research on the technological cultures of hacking in India.[4]

Charmed soap operatic analytics

I was recently introduced to a multimedia franchise called Charmed. Broadcast by Warner Bros. Television (aired between 1998 and 2006), the adaption of Charmed for television is a supernatural fantasy soap opera, mixing stories of relations between women and machinic alignments. Faced with the cognitive chaos of a hypermodern life in an imaginary San Francisco, as main characters of the soap, the three sisters-witches deal with questions of narcissism (self-oriented molar life-style), prosthesis (sympathetic magic as new technologies they have to learn to live with without mastering), global networks (teamwork with underworld), and dissatisfaction (nothing works out, relationships fail, anxiety attacks, and loneliness). In the series, ancient forms for life-sources, characterized as “demons”, are differentiated and encountered via the mediation of a technical life-source, characterized as “magic spells”. The technology is allegorically replaced by magic.

The soap presents the sisters, Prue, Phoebe, and Piper, oscillating between demon love and demon hate, and constantly negotiating the strange status of desire in general. These negotiations are fabled as the ongoing tensions between hedonism (to refuse to embody anxiety for polyamorous sexual life) and tolerance (the recognition of difference in the demons they must fight to the death) and those tensions are typically worked out melodramatically by the standards of the genre in the 1990s. The characters are frequently wrapped in and unwrapped by emotional turmoil, family discord, marriage breakdown, and secret relationships. They often show minimal interest in magic as a subject of curiosity, and instead they are more interested in spells as a medium through which their demons are externally materialized and enacted. Knowing has no effect on the protagonists’ process of becoming only actions. As such Charmed insists on putting “the transformation of being and the transformation of knowing out of sync with one another”.[5]

Past techniques of making species visible

The demons of Charmed are particularly interesting for multiple reasons. First, they are proposed taxonomically. Every demon is particular in its type, or subspecies, and classified per episode by its unique style of death. The demons are often mean-spirited aliens (men in suits), are less narrated in their process of becoming, and rather interested more in the classification of the manner of vanquishing them. They are “vanquished” at the end of each episode. To be more precise, exactly at minute 39, a demon is spectacularly exploded, melted, burned, or vaporized. One of the byproducts of this strange way of relating, is the Book of Shadows, a list or catalogue of demons and their transmodification. Lists are qualitative characteristics of cosmographical knowledge and my favorite specialized archival technology.

As a premodern cutting-edge agent of sorting, list-making was highly functional in the technologies of writing in the 12th and 16th century, namely monster literature, histoire prodigieuse or bestiaries. I have been thinking about bestiaries these past years, as one of the older practices of discovery, interpretation, production of the real itself. Starting off as a research project about premodern zoology in West Asia, Iran in particular, I found myself getting to know more about how “secularization of the interest in monsters”[6] happened through time. Bestiaries are synthesized sensitized lists of the strange. In them the enlisted creatures do not need to “stick together” in the sense of an affective or syntagmatic followability. That means they are not related narratively, but play non-abstract categories in their relentless particularities. A creative form of demon literacy, mnemonically oriented (to aid memorization), which is materialized in Charmed as the Book of Shadows. The melodrama affect of the series and emphatic lense on the love life of its cast-ensemble, allows a form of distance, making the demons becoming ontologically boring, which is paradoxically the subject of wonder literature (simultaneously distanced and intimate). On one hand the categorical nature of demons are anatomically and painfully indexed in the series, and on the other hand the romantic qualities of demonic life is explored.

Soap operas are among the most effective forms of linear storytelling in the 20th century, an invention of the US daytime serials. Characteristic of a soap operatic approach, is the use of the cast-ensemble, a collective of (often glamorous and wealthy) individuals who “play off each other rather than off reality”.[7] This allows the reality in which the stories go through to be rendered as an ordinary, constant, and natural stage. The soap often produces (and capitalizes on) a fable of reality, as that is the environment where multiple agencies are characteristically coordinated to face each other rather than their environment. Through the creation of banal and ordinary sites of getting on collectively in a romantic life, soup opera series are perhaps among the best tools to create cognitive companions (fans) and the sensation of ordinary affects, which are essential in “worlding” (production of the ordinary sense of a world).

The second reason to become interested in Charmed demons, is because of its visual effects. The disintegration effects of Charmed demon vanquishing can be perceived as “low tech”, meaning that its images develop a visuality that does not immediately integrate into high-end media in 2021. Its images, as I watched them in my attentive recognition (of a phenomena that is not complying with expectations) and partial attunement (to its explicit intensities), they cultivate my vision as the result of a perceiving organ. Why do I find demon species that depend on “expired” visualization technologies more interesting? This can be due to my own small resistance against new-media. Not a critical positioning, but more a sensation that has sedimented into an aesthetic taste (that is my consumption habit). The particular simulacral space of contemporary mediascape, with its preference for immersion, viscerality, interactivity, and hyperrealism, has to do with the way new-media makes meaning more attractive and (in a Deleuzian sense) less intensive. Charmed’s mythopoetic dreamscape now in 2021 has lost its “appeal”, therefore it is available to become tasty again. A witness to the gain and loss of attractivity in media culture is the process of fixing “bad” visual effects in the popular YouTube VFX Artists React series by Corridor Crew, in which the crew “react to” and “fix” the media affect of different VFX-intensive movies.[8]

Transmission of media affects

I have an affinity with disintegration effects. I remember from my early childhood trying to look at one thing for too long, and inevitable reaching a threshold at which that thing would visually break down and perception deteriorate. This was a game I used to play as a child, playing with attention and distraction, mutating myself into a state of trance or autohypnosis, absorbed, diverted, making myself nebulous. Through early experimentation with my own eyes as a visualization technology, within childhood’s world of the chaos of sensation, I sensed (or discovered) the disconnected nature of reality. This particular technoperceptual habituation might be behind my enduring attunement to simulacra and its disintegrative possibilities. The demons of Charmed are encountered via spell, metabolized, and then disintegrated. They become ephemeral phenomena, which accord with demonological accounts of them as fundamentally mobile creatures.

But perhaps I like Charmed demons mainly because of my preference for past techniques of making species visible, the business of bestiaries. In popular contemporary culture, the demon is an organism from hell, out of history (discontinuous with us). They are uncivilized incarnations of a threatening proximity not of this world. And who knows demons best today? The technical animators, working in VFX Industry, department of creature design. Computer technical animation is an undisciplinary microworld, situated in transnational commercial production for mass culture, where hacker skills are transduced to sensitized transmedia knowledge as they pass from the plane of heuristic techno-methodology to an interpretive plane of composing visual sense or “appeal”. To think of the space of a CG software, I am using Martha Kenney’s definition of microworld, a space where protocols and equipments are standardized to facilitate the emergence and stabilization of new objects.[9]

To get close to a lived texture of nonhuman nonanimal creatureliness, the technical animators have to sense the complexity of synthetic life through modeling (wealth of detail) and rigging (enacting structure). In other words, they need to get skilled at using digital phenomena (calculative abstraction) to create affectively positive encounters (appeal) with analogue body subjects that are irreducible to discrete mathematical states (the audience). This is a form of “open skill”,[10] a context-contingent tactically oriented form of understanding or responsiveness. Creature animation defined as such is, essentially, a hacker’s talent.

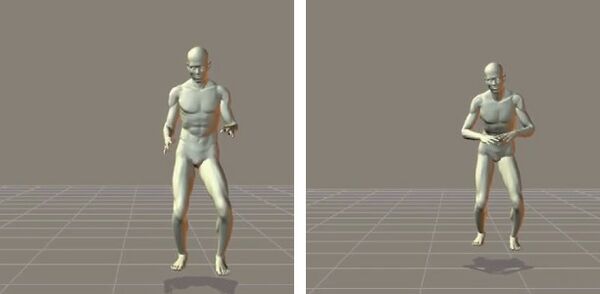

Following this understanding of technical animation, I want to highlight one of its actual practices as the focal point of interest in this writing, namely rigging. Rigging can be understood as staging and controlling “movement” within a limited computational structure (the microworld). Rigging is the talent associated with bringing an environment into transformational particularities using itself. It involves movement between the code space of the software environment (structural determination) and techniques they generate in response to that environment (emergent practice). In other words, the givens of computer graphics software are continually reworked in the creative responses CG hackers develop in relation to the microworld with which they interact. Rigging understood as such, is a workaround practice that both traverses and exceeds the stratified data of its microworld.

Rigging almost always involves making a quality of liveliness through movement. That means, technical animators, through designing so-called rigs, have to create an envelopment: a complex form of difference between the analogue (somatic bodily techniques as the source of perceiving movement) and the digital (analytical ways of conceptualizing movement). This envelopment (skin) reduces what is taken as a model to codified tendencies that encourage and prohibit specific forms of movement and action. As such, rigging is a technological site where bodies are dreamed up, reiterated, or developed.

Animal animation industry

In his research on the nature of skill in computer multiplayer games, James Ash suggests that the design of successful video games depends on creating “affective feedback loops between player and game”.[11] This is a quality of elusivity in the game’s environment and its mode of interaction with the players, which is predicated on management and control of contingency itself. This is achieved by interactively testing the relation between the code space (game) and the somatic space (users). Drawing on Ash’s insights, I would like to ask how affective quality of liveliness are distributed in the assemblages of various human and technical actors that make up rigging? Exploding demons; what kind of animal geography is that? This is a question of a non-living multi-species social subject in a technically mediated world. I follow Eben Kirksey’s indication of the notion of species as a still useful “sense-making tool”[12] and propose that the demon’s disintegrative body is a form of grasping species with technologies of visualization. In this case, rigging is part of the imagined species that is grasped through enacting (disintegrativity as its morphological characteristics).

Enacting is part of the material practice of learning and unlearning what is to be something else. To enact is to express, to collect and compose a part of the reality that needs to be realized and affirmed by the affects. To (re)enact something is a mutated desire to construct the invisible and mobile forces of that thing. Enactment is not just “making”, it is part of much larger fantasy practices and realities. The most obvious examples are religion and marketing as two institutions that depend on the enactments of fans (of God or the brand). The new-media fandom (collectivities of fans) venture in a social and collaborative engagement with corporate engineered products. But as Henry Jenkins has argued, this engagement is highly ambiguous.[13] Technical animators often behave like fans of their own cultural milieu. For instance when the Los Angeles based visual effects company Corridor Crew tells their story of fixing the bad visual effects of the Star Wars franchise, they enact a fan-culture by modifying and thus creating a variation. They participate in shaping a techno-cognitive context for engagement with Star Wars that operates the same story (uniform cultural memory) but has an intensity of its own (potential for mutation).[14] As we can see in the case of Corridor Crew, technical animation is always a materially heterogeneous work. The animators don’t sit on their desks, they enact all sorts of materialities. Animators use somatic intelligibility (embodiment) to fuse with their tools and become visual meaning-making machines that mutually embody their creatures. Therefore, the disintegration rig can be thought of as a human-machine enactment of a mixed-up species, a makeshift assemblage of human-demon-machinic agency enacting morphological transformations—bringing demon species into being. Doing demons is a social practice.

The animation industry is a complex set of talents and competencies associated with the distribution and transmission of media affects. Within VFX-intensive storytelling as one of the fastest growing markets of our time,[15] animation designers work to create artifacts potent with positively affective responses. The ways in which affect can be manipulated or preempted is a complex and problematic process.[16] Industrial model of distributed production is coalescence of conflicting agencies, infrastructures, responsibilities, skills, and pleasures where none of them is fully in command.[17] Animation technologies has evolved alongside the mass entertainment techno-capital market as a semi-disciplinary apparatus and its constituent player: fans, hackers, software developers, corporates, and pirate kingdoms. I prefer to use the term “hacker” (disorganized workaround practices) when referring to the talents of technical animators. CG hackers working in each other’s hacks and rigs, through feedbacked assemblages of skill sharing, tutorial videos, screenshots, scripts, help files, shortcuts. The assemblages are made of layers of codes and tools built on each other, nested folders in one’s own computer, named categories by oneself and others, horde of text files and rendered test JPGs, and so on. These are (en-/de-)crypting extended bodies of subjectively constructed through the communal technological fold interpreted as the 3D computer program. An ecology of pragmatic workaround practices that Amit Rai terms “collective practices of habituation”, which Katie King might call “distributed embodiments, cognitions, and infrastructures at play”.

I propose to understand CG hackers and technical artists with their practices of habituation, as craft-intensive. This implies understanding them as intimately connected with a particular microworld, the knowledge of which comes through skilled embodied practice that subsist over longer periods of time. I worked for some time as a generalist technical animator for both television and cinema, many years ago. An artisan’s life and a set of skills that I acquired in my youth, which are still part of my repertoire of know-hows that makes me expressive today. As many others have argued,[18] crafters attune to their materials, becoming subject to the processes they are involved in. Then, rigging as a skill can be understood as a form of pre-conceptual practice. By pre-conceptual I mean what Benjamin Alberti refers to as processes through which concepts find their way into actualities. Skilled practice is also the mark of the maker’s openness to alterity.[19] An alterity in relation to that which the machinic entity becomes quasi-other or quasi-world.[20] Is it possible to invoke epistemological intimacy (a way of grasping one’s own practice) through the processes of crafts? What is Charmed’s answer to this?

Demon disintegration zoomorphic writing technology

CG stands for computer graphics, but also for many more things, computational gesture, and creature generator. In the example of demon disintegration that I gave earlier, I suggested the presence of zoomorphic figures (demons) as an indication for thinking about rigging as a bundle of the digital (calculative abstraction), the analogue (body appeal), and the nonhuman (zoomorphic physiology). Zoomorphic figures are historically bound with animation technologies. The design and rigging of “creatures” are part of every visual effects training program and infused in the job description. Disney Animation Studios is the example of critical and commercial success through mastery over anthropomorphized machines. Animation has been a technology of zoomorphic writing.

Automata and calligraphy’s mimetic figures

Zoomorphic writing technologies are not new. The clockwork animals, those attendant mammalian attachments, were bits of kinematic programming able to produce working simulacrums of a living organism. Perhaps rigging is a manifestation of the desire to produce and study automata. For Golem, that unfortunate unformed limb, the rig was YHWH, the name of the God. Another witness is a variation of calligraphy, the belle-lettre style of enfolding animals into letters, which is as old as writing itself. The particular volumetric regime of making animal shapes with calligraphy operates by confusing pictorial and lexical attributes, mobilizing a sort of wit in order to animate imaginary and real movements. Mixing textuality and figurality is something like a childhood experience. A kind of word-puzzle which uses figurative pictures with alphabetical shapes. It is a game of telescoping language through form, schematizing a space where the animal’s body and language form one gestalt. In my childhood I was indeed put into a calligraphy course, which I eventually opted out of. Although extremely short, my calligraphy training taught me how the world passes through the mechanized, technical, and skillful pressure of the pen, hand, color, paper, and eye as an assemblage. At that time I experienced calligraphy as an entirely uncharismatic technology. Yet I found myself spending endless hours making mimetic figures with writing. I felt how making animals with calligraphy conflates language and image and thus makes it liable to move in many unpredictable directions. The power of the latent, the hidden relationships, the interpretable. A state of multistability that I enjoyed immensely as a child.